The invoice looks simple: an itemised list, totals, a due date — but behind that simplicity lies one of humanity’s oldest acts of civilisation: recording value. Long before currency notes, balance sheets, or accounting software, the act of writing down a transaction transformed trust into something tangible. It bridged the gap between memory and accountability, between spoken promise and measurable exchange.

Every society that has ever traded, bartered, or shared resources eventually discovered the same truth: memory alone could not sustain trust at scale. To ensure fairness, communities learned to inscribe agreements — not to glorify bureaucracy, but to preserve honesty. The invoice, in its earliest form, was not a corporate artifact; it was a moral technology. It recorded not just numbers but relationships — who owed whom, for what, and why.

What began as clay and ink would become the foundation of credit, contracts, and even national economies. The humble invoice carries within it the DNA of civilisation itself — a record that both empowers and equalises, giving weight to words and memory to trade.

1. Origins of Value & Record-Keeping

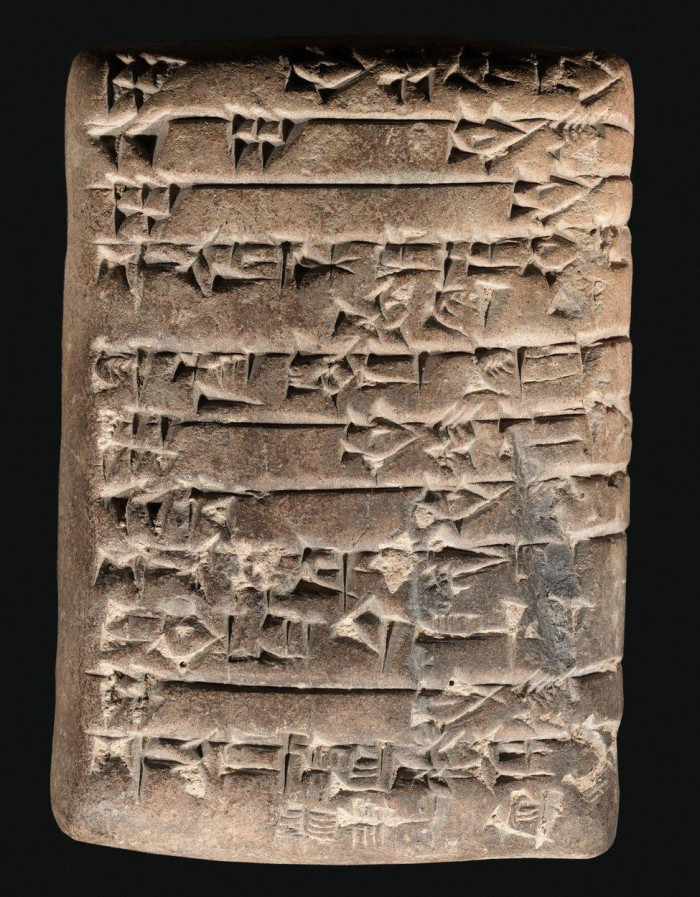

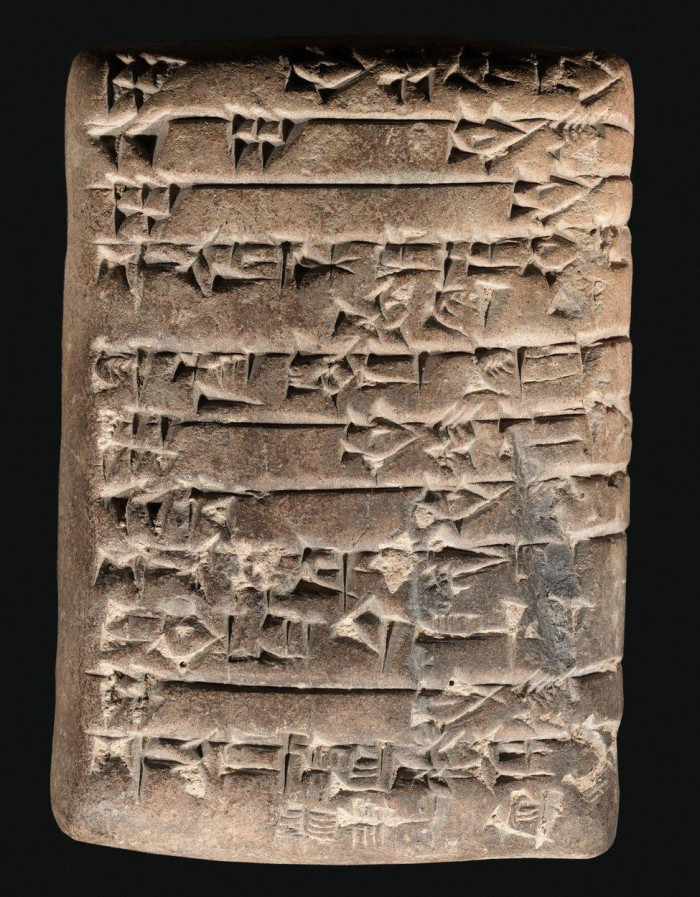

Archaeologists have uncovered thousands of clay tablets from the ancient city of Uruk — the cradle of Mesopotamian civilisation, around 3,500 BCE — etched with small wedge-shaped marks known as cuneiform. Uruk stood in what is today southern Iraq, near the Euphrates River (modern Warka, in Al-Muthanna Governorate). Among these tablets are records of grain deliveries, wool shipments, and temple accounts — some of the world’s earliest invoices. Each symbol represented a quantity, a commodity, and a recipient. These were not art pieces but administrative tools: hard evidence that a transaction had taken place.

This was a revolution. For the first time, value could be detached from the presence of its maker. The clay tablet became a surrogate for trust — portable proof that allowed merchants and farmers to trade even when apart. In this way, accounting and writing evolved side by side; writing did not arise from poetry or myth, but from the need to track a debt. The world’s first bureaucrats were not kings but clerks.

Similar practices emerged independently across other civilisations. In ancient Egypt, scribes used papyrus to log taxes and deliveries for the Pharaoh’s granaries. In early China, bamboo slips and silk scrolls recorded imperial levies and merchant exchanges. In the Aegean, Linear B tablets preserved inventories of oil, honey, and bronze long before the Greek alphabet existed. Everywhere humanity built settlements, record-keeping followed — as if written documentation were the invisible scaffolding of trust.

Across these cultures, the first accountants were also spiritual intermediaries — scribes who stood between humans and gods, ensuring that offerings were measured and duties fulfilled. Their ledgers were sacred as much as practical, for imbalance was not only an economic failure but a cosmic one. Through these early invoices, humanity learned that justice in trade required evidence, and that prosperity depended on precision.

2. Evolution of Forms & Legitimacy

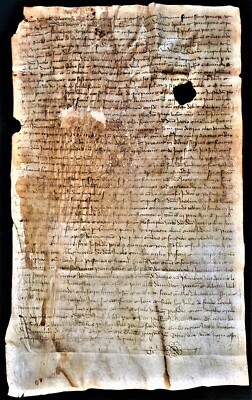

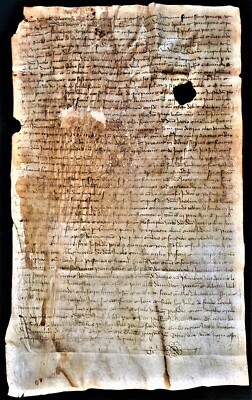

As trade routes stretched across the Mediterranean and into the North Sea, merchants of the Middle Ages began to face a new challenge: how to prove legitimacy across distance. A bill of sale scribbled in Genoa needed to be honoured in Bruges, a tally stick cut in London had to be trusted in Florence. The solution was not military power or royal decree — it was paperwork. The handwritten invoice became both a passport and a promise.

Within the merchant guilds of Europe, these records evolved from informal notes into carefully formatted instruments. The rise of double-entry bookkeeping in fourteenth-century Italy — championed by figures such as Luca Pacioli — gave every transaction a mirror image: debit and credit, claim and proof. This symmetry introduced a new idea to commerce: that honesty could be demonstrated mathematically. The invoice, once a scrap of parchment, now carried the weight of an entire moral philosophy — a balance between giving and receiving.

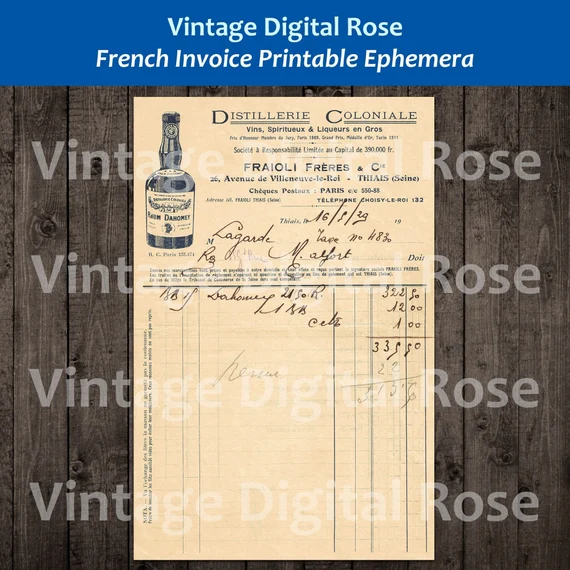

By the fifteenth century, the printing press brought an administrative revolution. Merchants and clerks no longer copied forms by hand; presses in Venice, Antwerp, and London churned out pre-ruled ledgers and invoices with headings like “To Mr. …” and “Received this day …”. Typography became a tool of trust: standard fonts and consistent columns signalled order, literacy, and accountability. A uniform page layout was itself a mark of legitimacy.

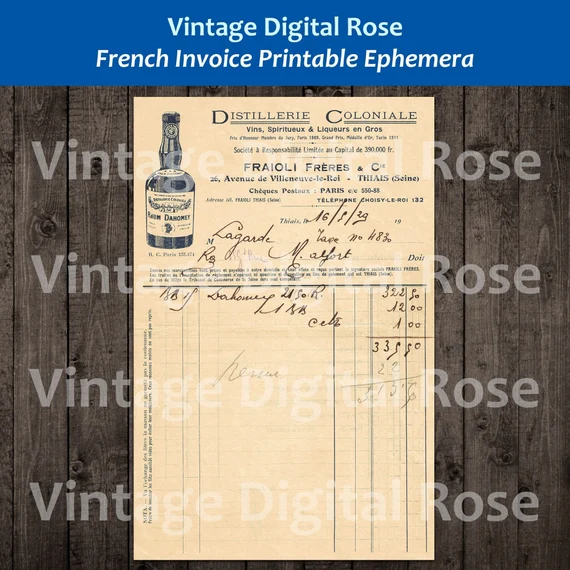

As empires expanded and corporations emerged — the East India Companies, the Hudson’s Bay traders, the great shipping houses of Liverpool and Amsterdam — the invoice became an emblem of power. Its language codified the world: quantity, weight, measure, price, and seal. The paper trail was no longer a humble record but a legal artefact linking dockyards, counting houses, insurers, and courts. An unpaid invoice could now cross oceans and demand justice in the name of law.

The Industrial Revolution amplified everything. Machines produced more goods than any one city could consume, and millions of new invoices connected manufacturers, distributors, and customers across a web of contracts. Each printed form became a thread in the first truly global network — not of wires or radio, but of promises written in ink. An invoice was the internet of its age.

3. Access, Schooling & Divides

By the eighteenth century, the invoice was everywhere — yet access to its power remained a privilege. To send or even understand one required more than honesty: it required literacy, numeracy, and a place within the networks that recognised paper as proof. In cities, merchants and clerks built their lives around ink and ledgers; in rural or colonised regions, many worked, produced, and traded daily without ever seeing their labour represented on a page.

In early modern Europe, the ability to write an invoice or sign a receipt often marked the boundary between citizen and subject. Guild apprentices learned to copy prices and terms long before they could vote or own land. Across oceans, enslaved and indentured labourers generated immense wealth, but the value of their work circulated only in other people’s handwriting. The document that guaranteed fairness for some became the tool that erased others.

Education was the great divide. When missionary schools and colonial administrations spread literacy, they also decided whose literacy counted. A trader in Lagos or Kingston might speak five languages, bargain flawlessly, and remember years of transactions — yet without access to “proper” English script, his knowledge was dismissed as informal. The paperwork of power required not only knowing but knowing in the sanctioned way. A pen was a passport; a spelling error could be a border.

Even within industrial societies, schooling stratified access. Women who ran shops or family enterprises often relied on male relatives or scribes to draft bills. Artisans who could craft a masterpiece by hand might still need someone else to document its sale. The invoice therefore mirrored the structure of society itself — a hierarchy of handwriting, where education, class, and gender decided who could participate in the written economy.

4. Invoices in the Global Economy

By the nineteenth century, the invoice had outgrown its local purpose. Steamships, telegraphs, and colonial expansion bound the world together in a single network of trade — and with it came the globalisation of paperwork. An invoice written in Manchester could now travel to Bombay, Cape Town, or Kingston and return with payment, interest, and legal standing. The language of commerce became a lingua franca that transcended tongues but preserved hierarchies.

The rise of the British Empire and other industrial powers turned documentation into a weapon of efficiency. Railways, plantations, and factories were all fuelled by record-keeping: manifests, bills of lading, ledgers, and invoices. Yet behind their neutral appearance lay an asymmetry — those who issued the papers controlled the profit; those whose labour filled the papers were rarely named. Entire colonies operated under what historians now call the paper empire, where bureaucracy and bookkeeping governed lives more tightly than any army.

Currency and measurement became part of this system. Pounds, francs, and dollars replaced cowries, manillas, and barter credits, redefining value through Western standards. To trade internationally, one had to invoice in the language — and currency — of empire. Even after independence, many nations found their commercial systems tied to these inherited templates. The fonts, the ledgers, even the filing cabinets spoke the grammar of colonial administration.

As the twentieth century advanced, banks and corporations mechanised invoicing through typewriters, carbon paper, and later, computers. The new efficiencies masked old imbalances. Where infrastructure and legal frameworks were strong, invoices ensured swift settlement; where weak, they became paper promises waiting on broken systems. A missed stamp, a lost form, or an unrecognised signature could strand a small trader for months.

The digital revolution promised to level the field, yet access still decides who benefits. Reliable internet, payment gateways, and legal recognition of e-signatures remain uneven worldwide. The difference between a paid invoice and an ignored one can still trace the same centuries-old boundaries: connectivity, literacy, and trust.

5. Reclaiming the Invoice

After centuries of serving kings, merchants, and empires, the invoice has finally returned to the hands of individuals. What was once a tool of bureaucracy can now be a symbol of freedom. For the self-employed artist, the local tradesperson, or the independent engineer, issuing an invoice is not simply a request for payment — it is an act of self-recognition: a declaration that my work has measurable worth.

The digital era has made this possible. Software can now automate what once required entire offices of clerks. Templates, tax calculations, and currency conversions happen instantly, removing the intimidation that kept so many from formal commerce. A single person can send a document with the same precision and authority once reserved for corporations. Technology has turned record-keeping from a gatekeeper into a guide.

Yet true progress lies not in convenience alone but in understanding. When a creator learns the rhythm of invoices — due dates, references, and reconciliations — they begin to read the invisible architecture of the economy. The ability to document one’s labour is a civic power, not just an administrative skill. Each invoice sent by a freelancer, teacher, or small business owner is a statement of equality within a system that once excluded them.

Platforms such as Algorithm Invoice exist to amplify that shift: teaching the language of commerce while restoring dignity to those who work outside the old frameworks. By blending automation with clarity, the software becomes not a faceless app but a modern scribe — ensuring that creativity, craft, and independent effort are never lost in the noise of big systems.

6. Language Note on “Black”

Words carry worlds within them. Over centuries, the word “black” has travelled a long and complex route — from describing the colour of ink and fertile soil to symbolising shadow, secrecy, and finally, identity. Its early meanings were neutral, even sacred: in ancient Egypt, Kemet, the “black land,” referred to the rich, dark earth nourished by the Nile. In medieval Europe, “black letter” described the dense, elegant script of monastic texts. The colour represented permanence — the mark that could not be erased.

But as printing, commerce, and literacy spread, the semantics of black began to shift. The phrase “black work” once referred to undocumented or off-the-books labour; “black market” to unlicensed trade; “blacklist” to exclusion. These terms arose not from skin colour but from the visual logic of ink on paper — what was written down (in light) was legitimate, what remained unwritten (in dark) was not. Over time, however, this metaphor hardened into hierarchy.

In societies where literacy determined worth, “black” came to symbolise not only opacity but absence: absence of education, permission, or proof. Those who could not sign their name were said to “make their mark,” often an “X” — a ghost of identity on paper. As colonial expansion and the slave trade imposed European languages on the world, this symbolic darkness was mapped onto people, turning metaphor into prejudice. What had once meant “unrecorded” came to mean “unworthy.”

The tragedy of this linguistic evolution is that it confuses colour with competence, pigment with participation. A term born from the material of ink and writing — from the very tool that allowed trade and civilisation to flourish — became a label for exclusion. Yet language, like the societies that speak it, can evolve again. To write, to invoice, to record, is to reclaim the right to define oneself in one’s own ink.

7. Why This Matters & What’s Next

The invoice may appear mundane — a slip of numbers, a line of text — yet it represents one of humanity’s greatest inventions: the ability to give value a voice. To document is to affirm existence; to invoice is to say, this work happened, and it matters. Every entry in a ledger, from clay tablet to spreadsheet, tells the same story: civilisation survives because we remember who contributed.

Across millennia, the act of recording value has always reflected the health of a society. When only a few could write, wealth concentrated around their pens. When literacy spread, so did prosperity. In today’s digital age, the same pattern repeats: access to tools determines access to fairness. Software, broadband, and transparent systems are the new ink, and they decide whose voices echo in the economy.

The challenge of our time is not creating new technology — it is ensuring that technology serves everyone. A system that merely automates exclusion is no improvement at all. But when design meets empathy — when clean code meets clear conscience — technology can restore what history distorted: equal visibility. The screen becomes a new parchment, and a digital invoice becomes a declaration of belonging.

This is where Algorithm Invoice continues the human story. It is not just software; it is an educational bridge, a translator between creativity and commerce. By simplifying process and language, it gives individuals the confidence once reserved for corporations. Each invoice generated through the platform stands as a digital heir to every scribe, trader, and craftsman who ever marked their worth in clay or ink.

The next frontier lies in connection — linking artists, entrepreneurs, and independent workers across borders with shared standards of trust. Imagine a world where a musician in Lagos, a designer in São Paulo, and a teacher in Southampton can transact instantly with equal credibility, each supported by a transparent record. The future of fairness is not charity; it is infrastructure.

8. From Granada to Global Colour Lines

The year 1492 marked a profound rupture in human history. When the Nasrid kingdom of Granada fell to Ferdinand and Isabella, it ended nearly eight centuries of coexistence in Al-Andalus — a period when Muslim, Jewish, and Christian scholars had traded ideas as freely as merchants traded goods. What followed was not only conquest but purification: a systematic rewriting of identity and worth. Within months, Spain expelled its Jewish population, forced conversions among Muslims, and financed voyages that would redraw the world.

The new age of empire demanded new paperwork. The same printing presses that once spread scripture and science now printed decrees, licenses, and proofs of bloodline. Bureaucracy became theology by other means. Ink replaced sword — yet its impact was no less absolute. A person’s faith, ancestry, or colour could be certified or condemned by a few lines on paper. And paper, unlike stone, is fragile: a single flame, a royal edict, or a revision of the archive could erase generations. The power to destroy paper became the power to destroy people’s place in history.

Across Europe and its colonies, this fusion of faith, colour, and commerce hardened into ideology. The discovery of new lands required moral justification, and so difference became doctrine: lightness equated to purity and divine favour; darkness to sin and servitude. In art, pale saints and dark devils mirrored a new racial grammar that would seep into trade itself. Fabrics, spices, and even skin were classified as commodities, and the same ledgers that tallied sugar and gold began to list human lives.

Yet beneath this transformation lay irony. The printing press — Europe’s proudest tool of enlightenment — had emerged only decades earlier from the same Rhineland workshops that once supplied Granada with paper and ink. The technology that could have unified knowledge was instead enlisted to codify difference. Still, the press also sowed seeds of rebellion: pamphlets, abolitionist tracts, and underground newspapers would later turn that same ink against tyranny.

Thus the invoice, the ledger, and the certificate — descendants of the ancient tablet — became instruments in both directions: oppression and liberation. Every era faces the same choice: to use record-keeping as a mirror of hierarchy or as a blueprint for equality. The lesson of Granada is not merely about religion or empire; it is about what happens when the control of documents replaces the search for truth.

9. The Colour of Commerce & the Commerce of Colour

After Granada, Europe’s appetite for wealth turned outward. Exploration became extraction, and commerce became conquest. Ships left Lisbon, Bristol, and Seville laden not only with goods but with ledgers, stamps, and seals — the instruments of a new bureaucracy that would define entire continents. Colour, which once belonged to art, cloth, and nature, was transformed into a category of ownership.

Colonial expansion embedded these hierarchies deep within the machinery of trade. Ledgers and invoices no longer measured only cargo; in many systems they measured people — their labour, their bodies, and the monetary value assigned to their existence. On the docks of Kingston, Charleston, and Bahia, auction lists looked indistinguishable from cargo manifests. Racism became bureaucratised; prejudice gained paperwork. To be enslaved was to appear in ink but vanish in name.

Yet the same paper trail that recorded oppression also became evidence of it. Abolitionists, lawyers, and freedpeople later used those ledgers as proof — receipts of injustice that no government could deny. The invoice, the bill of sale, and the manumission certificate turned into witnesses in court. The oppressor’s pen unwillingly became the historian’s ally.

Across the Caribbean and the Americas, formerly enslaved artisans and traders began to issue their own documents of legitimacy — bills, contracts, receipts — asserting economic agency in the very language that once erased them. These self-written records were revolutionary: declarations of equality disguised as paperwork. To sign one’s name, to stamp a mark, to send a letter of account was to reclaim humanity through ink.

The industrial age extended these colour lines through global supply chains. Cotton grown by coerced labour in the South was milled in Manchester and sold back across the world. Sugar, coffee, and indigo — commodities prized for their whiteness, darkness, and brightness — embodied the moral contradictions of modernity: luxury built on bondage. The economics of shade became the economics of status.

And yet, through every century of exploitation, people found resistance in record-keeping itself. Letters of freedom, cooperative account books, and petitions for wages filled new archives of defiance. The written word — once an emblem of empire — evolved into a weapon of emancipation. History’s margins were no longer empty; they were being rewritten by those who had lived between its lines.

10. Restoring Meaning in the Modern Age

Today, the invoice can once again reclaim its original, noble purpose — a document of equality. Stripped of bureaucracy and ornament, it returns to what it was always meant to be: a written acknowledgment that every person’s labour carries weight, and that value deserves recognition. Whether it is a hand-drawn sketch, a song produced in a home studio, or a service rendered across continents, the simple act of documenting it restores dignity to the exchange.

We live in an age when paperwork has become digital dust — PDFs in inboxes, receipts in clouds, transactions processed in seconds and forgotten just as quickly. Yet the principle remains unchanged: the record matters. To write an invoice is to leave a trace, to say, “I was here, and my contribution had worth.” The danger of automation is not that it replaces effort, but that it can make human work invisible behind algorithms and platforms that never speak our names.

That is why intention matters as much as innovation. Software, automation, and artificial intelligence can either replicate history’s inequities or repair them. They can turn paperwork into faceless compliance — or into community. Every digital form carries a moral question: will it record fairly, or merely repeat exclusion in a faster font? Technology itself is neutral; the ethics of those who design it are not.

When an artist, entrepreneur, or small business owner issues an invoice through a platform like Algorithm Invoice, they participate in a living tradition older than money and newer than code. They join the lineage of scribes, traders, and creators who refused to let their work go uncounted. Each document generated becomes a tiny monument — evidence of effort, artistry, and self-determination. The platform’s purpose is not just calculation, but conversation: a dialogue between centuries, reconnecting humanity’s oldest record-keeping with its newest tools.

In this light, the invoice becomes more than a bill; it becomes a bridge — a line drawn across time. From clay tablets buried in the dust of Uruk to glowing screens in modern studios, the same impulse endures: to give form to fairness. Every time we record our worth truthfully, we repair a small fragment of the past. Every time we pay someone honestly, we restore balance to the present. And every time we build systems that respect all contributors, we write the future differently.

Image References

Thank you for taking the time to read this history. Every visitor who learns the story behind the invoice helps preserve a truth older than money itself: that fairness begins with documentation. — Dr Dennis J. Gordon